Here’s a quickie literacy lesson for any subject that is backed by evidence and research

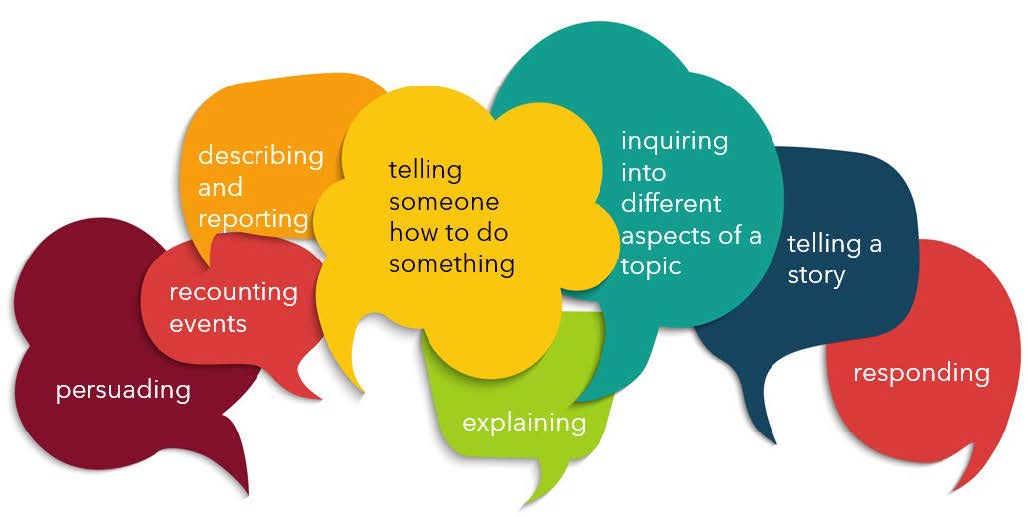

It’s a quick Teaching and Learning Cycle that should take around 20 minutes. Since it’s short, we will be asking students to write a short paragraph of around 3 sentences… but they will be good sentences.

Teacher preparation before the lesson

- Find 3 related things to write about on your topic, such as:

- Explain 3 causes or 3 effects of something

- Interpret three sources about the same topic

- Describe three designs

2. Prepare a model text

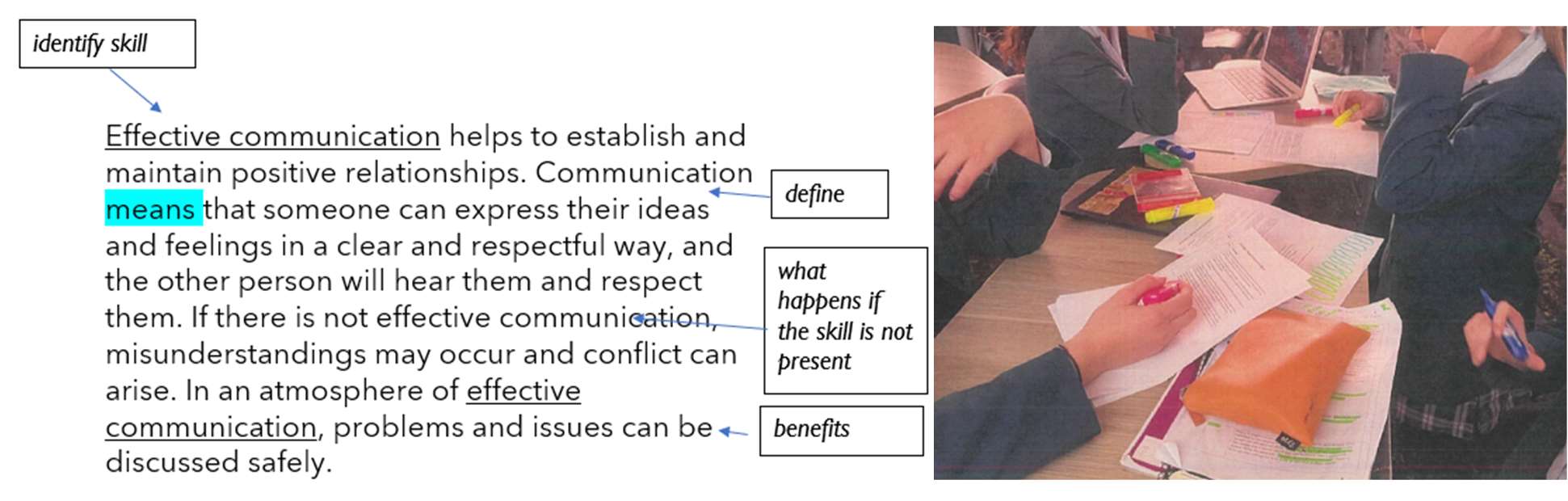

Write a model text of a few sentences about ONE of the things e.g. one cause, one effect, one source, one design. Identify the features that students will annotate (e.g. the job of each sentence, cause and effect language for explaining, technical terms for descriptions, meaning verbs for sources ie shows, means, reveals, illustrates)

Print one paper copy of the model text for each student. You should be able to fit several on one A4 page.

During the lesson

- Do a pre-test.

Give students a piece of paper and ask students to write about the a topic/image/ stimulus without any support. This is the pre-test and it’s not supposed to be good. I’ve seen students write a few words or nothing at all for a pre-test and that’s fine.

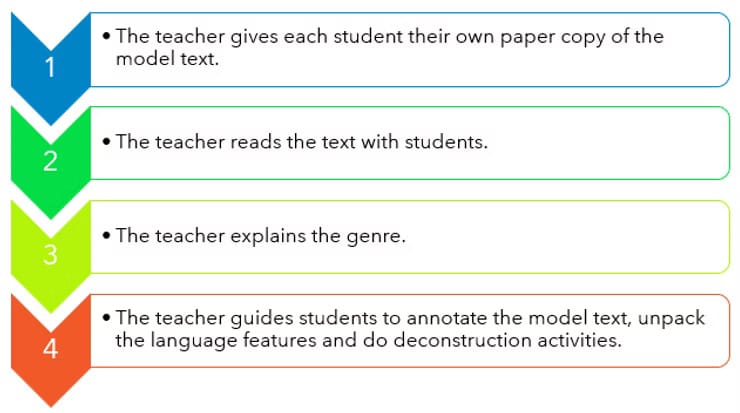

2. Modelling

Give out the paper model texts. Read the text and ask students to annotate with the features you prepared.

3. Supported writing

Give students the second topic, second source or second design. Ask them to write a text with a peer in pairs or groups using the same features as the model text.

4. Independent writing

Give the students the first topic again, the one they did in the pre-test. That’s the independent text. Ask them to re-write their text now that they know what to do.

5. Evaluate

Ask students to swap their text with a peer and evaluate how much the text has improved. It could be longer, contain more technical terms, be more accurate. It should be a positive experience and you can discuss how much the students have improved.

If you do this activity regularly, I swear that you’ll see improvement in your students’ confidence and ability to write like subject experts.